Mobile security goes beyond verifying user identity. If an attacker steals a valid token, how will your backend distinguish a legitimate request from one reproduced in an emulator or cloned environment? This is a gap in traditional authentication flows when applied to the mobile environment.

By linking each request to hardware-backed keys generated during secure device registration, it’s possible to strengthen the chain of trust and reduce the possibilities of external attacks on the device.

In this blog post, we show how a device-bound, proof-of-possession-based signature mechanism can offer more robust protection with minimal impact on performance and user experience.

Why Traditional Authentication Is Not Enough for Mobile Security

Mobile apps have become the primary gateway to digital services, powering financial transactions, healthcare access, government interactions, and enterprise workflows. As the sensitivity of these operations increases, so does the risk of off-device threats. Attackers who gain access to valid credentials or session tokens can exploit them from unauthorized devices, bypassing authentication safeguards and impersonating legitimate users.

User authentication mechanisms such as OAuth/OIDC, MFA, and session tokens perform their intended role effectively by verifying who the user is. However, these mechanisms do not verify which device is generating each request. Device identity and integrity represent a separate and critical layer of trust, given that even valid credentials can be reused, replayed, or exploited from untrusted, cloned, or compromised environments.

Transport protections like mTLS, TLS pinning, and payload encryption strengthen channel confidentiality and integrity, yet they still leave an open question: Can the backend cryptographically verify that a request was generated by the legitimate, enrolled device? Recent standards such as DPoP (Demonstrating Proof of Possession) and device-bound session credentials reflect this same shift toward sender-constrained credentials and proof-of-origin at the request level.

To address this challenge, Device-Bound Request Signing (DBRS) provides a complementary approach that cryptographically binds API requests to their originating devices, ensuring verifiable proof of origin in a layered trust model.

Establishing Cryptographic Chain of Trust

As trust moves beyond simple authentication, the greatest challenge becomes when and how that trust is established. The issue is not in the cryptographic protocols themselves, but in the initial moment of trust: when a new device enrolls and the backend must determine whether to trust the environment presenting the credentials. This first key exchange, often conducted over the public internet, becomes a high-value target. If it is compromised, every subsequent proof, no matter how robust, rests on a weak foundation.

After initial registration, maintaining trust securely across sessions, app reinstalls, and OS updates introduces additional complexity. Cryptographic keys must remain bound to the enrolled device, requests must be verifiable on a per-device basis, and the backend must continuously validate that each request originates from the expected context while maintaining smooth user experience and acceptable performance.

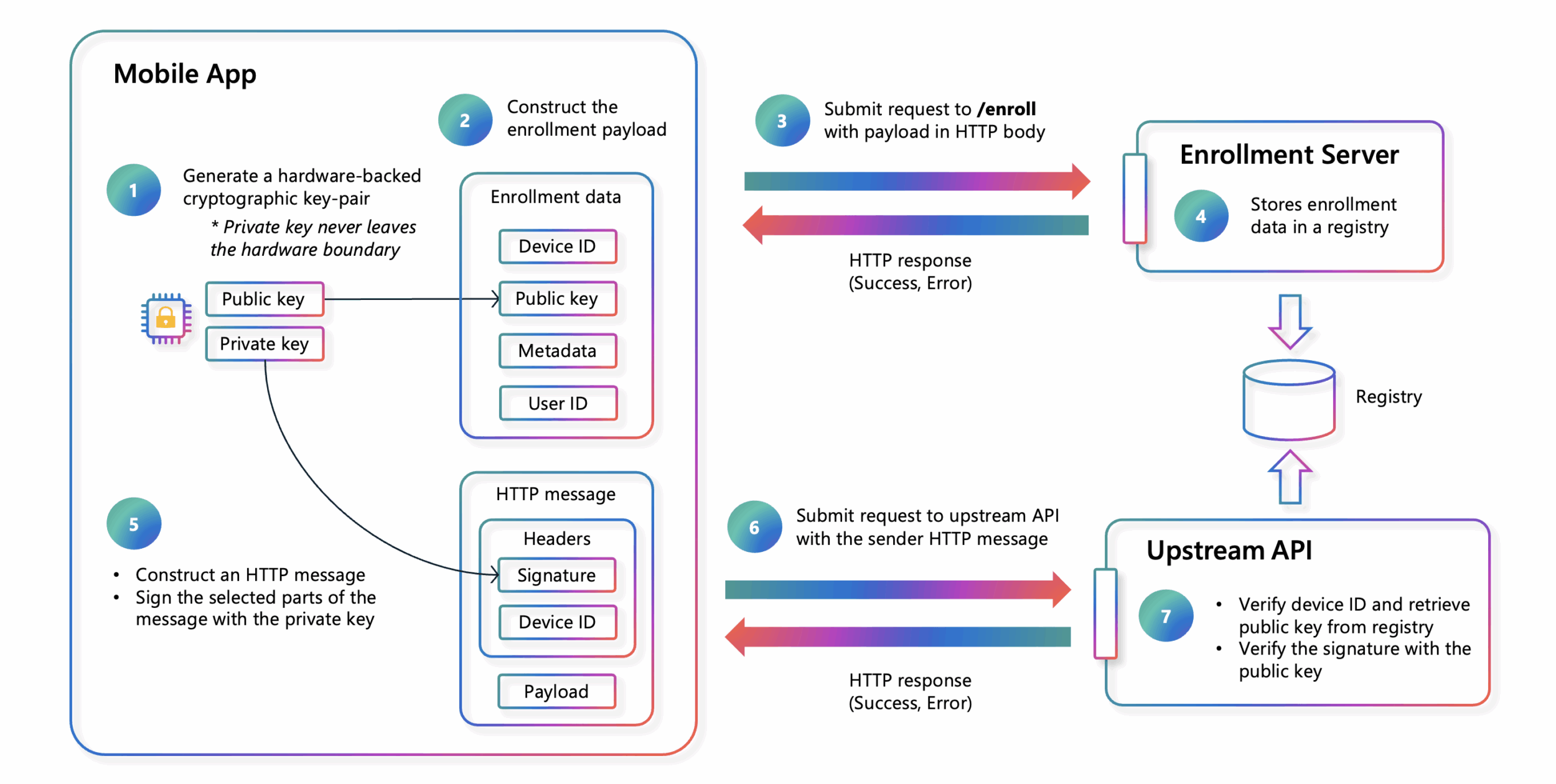

This is where Device-Bound Request Signing (DBRS) fits in. It provides a consistent, lightweight method to assert that every request originates from the same legitimate device enrolled initially, turning the fragile first registration into a durable proof of possession that persists throughout the app lifecycle. The following diagram provides an overview of the flow:

- Hardware-backed key generation: When users install and authenticate in the app for the first time (or after reinstall), the device goes through secure enrollment, generating cryptographic key pairs directly in hardware enclaves (iOS Secure Enclave, Android Keystore). These private keys are non-exportable and cannot be accessed by software, ensuring only the original device can produce valid signatures. This process binds device identity, public key, and user identity, establishing a root of trust.

- Cryptographic proof of possession: After enrollment, every API request is signed with the device’s private key, creating unforgeable proof of origin. Because private keys never leave the hardware enclave, attackers cannot extract or forge valid signatures outside the enclave, even with root access or full control of the application layer. Each request carries cryptographic proof it originated from a trusted device and verified user.

- Backend verification: Backend services perform a lookup of the device ID in a device registry to retrieve the device’s public key and metadata, then verify the signature against registered public keys. Based on these checks (signature validity, device status, risk signals, and policy), the backend confirms both user identity and device authenticity, then accepts or denies the request. This allows backends to verify not just the app, but the physical device making the request.

Use Cases

- Operating in regulated industries (e.g. finance, healthcare, government) with strict compliance requirements

- High-value transactions where the cost of fraud justifies additional security controls and architecture complexity

Securing the Enrollment Process

- Step-up authentication during enrollment

-

- Require additional verification factors specifically for device enrollment (e.g., biometric verification, email/SMS OTP, push notification to existing trusted device)

- Apply stricter authentication requirements than regular login flows

- Key attestation during enrollment

-

- Modern platforms (iOS DeviceCheck, Android Key Attestation) allow the device to prove at enrollment time that a key was generated in hardware

- The backend can verify this attestation and trust that the enrolled key is hardware-bound

- Attestation provides cryptographic proof that the private key was created in a secure hardware enclave and cannot be extracted or duplicated

- Reject enrollment attempts from devices that cannot provide valid attestations or show signs of compromise (e.g., unlocked bootloader, modified system)

- Device intelligence and risk scoring

-

- Evaluate device attributes during enrollment: OS version, security patches, jailbreak/root detection, emulator detection

- Analyze behavioral signals: unusual geolocations, suspicious timing patterns, multiple failed enrollment attempts

- Implement velocity controls: limit the number of devices that can be enrolled per user within a time window

- Flag high-risk enrollments for manual review or additional verification

- Existing device notification

-

- When a new device attempts enrollment, send push notifications to all previously enrolled devices

- Allow users to block enrollment from their existing trusted devices

- Implement a cool-down period before new devices gain full privileges

- Enrollment approval workflow

-

- For enterprise or high-security contexts, require administrator or security team approval before completing enrollment

- Implement time-delayed activation where new devices enter a “probationary” period with limited privileges

- Allow organizations to pre-register device identifiers (IMEIs, serial numbers) to create an allowlist

- Post-enrollment monitoring

-

- Continuously assess device health and trustworthiness even after enrollment

- Implement anomaly detection for unusual patterns from newly enrolled devices

- Provide users with visibility into all enrolled devices and the ability to revoke devices remotely

Additional Design Considerations

- Algorithms: Select cryptographic algorithms that strike the right balance between security, performance, and compatibility.

- For mobile environments, ECDSA (ES256) and Ed25519 are preferred due to their fast signing times, smaller key sizes, and broad hardware acceleration support. However, RSA may still be required to maintain interoperability with legacy systems.

- Looking ahead, it is important to begin researching and prototyping post-quantum signature schemes such as ML-DSA, SLH-DSA, and FN-DSA, which are expected to become the next NIST-approved standards for digital signatures. The migration to quantum-resistant cryptography is no longer theoretical; it is a practical inevitability that organizations must plan for in the coming years.

- Caching: Use server-side caching for device registry lookups and public key retrieval to minimize latency and reduce load on backend databases.

- Compatibility: Ensure support for hardware-backed key storage across target devices and OS versions. Supporting legacy devices without hardware security features requires fallback mechanisms that weaken security guarantees. Implement software fallbacks for older devices, but apply stricter risk policies when hardware security is unavailable.

- Observability: Track key metrics, logs, and traces for enrollment, signing, and verification. Set alerts for failures or latency spikes. Protect privacy by hashing device IDs and redacting sensitive data.

Tradeoffs and Pitfalls

Complexity and Development Cost

- Increased development effort: Implementing cryptographic operations, key management, and device enrollment across mobile platforms requires specialized expertise and testing.

- Maintenance burden: Managing key rotation, device registry operations, and signature verification logic adds ongoing operational overhead.

- Cross-platform consistency: Ensuring identical security guarantees across iOS and Android despite different hardware security APIs and capabilities.

Performance

- Latency overhead: Every request incurs cryptographic signing (client-side) and verification (server-side) operations, adding milliseconds to response times.

- Battery consumption: Frequent cryptographic operations, especially on older devices without hardware acceleration, can impact battery life.

- Network overhead: Additional headers for device ID and signatures increase request size.

Operational Risks

- Registry availability: Device registry becomes a critical dependency; downtime or latency issues can directly impact all API requests.

- Key compromise recovery: If a device’s private key is compromised (e.g., through rooting/jailbreaking), revoking and re-enrolling requires robust incident response procedures.

Limitations

It’s important to note that implementing Device-Bound Request Signing (DBRS) should not be viewed as sufficient for protecting against other threat vectors common to mobile applications (e.g., runtime manipulation, code injection, social engineering, phishing, malware on the device, excessive privileges, or vulnerabilities in business logic). Similarly, DBRS does not protect against attacks that occur before device enrollment, such as account takeover or credential compromise during initial registration.

While DBRS provides cryptographic proof that a request originated from a specific enrolled device, it cannot prevent misuse by legitimate device owners acting maliciously, nor can it detect all forms of device compromise (e.g., sophisticated malware running with elevated privileges that manipulates the user into performing unauthorized actions).

Applying DBRS should not be viewed as a finish line for mitigating risk. Designs that implement DBRS can still be prone to failure (e.g., a user with a compromised device performing legitimate but fraudulent transactions, or an attacker with physical access to an unlocked device), and defense in depth is a critical component towards mitigating the highest risk scenarios when the failure of a single layer may be likely.

DBRS is a supplement, and not a substitute, for common security principles such as least-privilege, zero-trust architecture, continuous authentication, behavioral analytics, transaction monitoring, and runtime application self-protection (RASP). Organizations should view DBRS as one layer in a comprehensive security strategy that includes secure development practices, threat modeling, penetration testing, and incident response capabilities.

STRIDE: Threat Model Analysis

| STRIDE Category | Threat Type | Primary Risk in Mobile/API Context | DBRS Mitigations | Remaining Gaps / Complementary Controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S – Spoofing (Identity Forgery) | An attacker impersonates a legitimate user or device (e.g., replaying stolen tokens or using cloned apps/emulators). | API requests could be accepted with valid credentials originating from unauthorized devices. |

|

|

| T – Tampering (Data or Code Manipulation) | Modification of app code, API payloads, or interception of data before signing. | Attackers could alter payloads or app logic prior to cryptographic signing, undermining data integrity. |

|

|

| R – Repudiation (Denial of Origin) | A user or attacker denies having performed a legitimate operation. | Difficulty in proving that an API call originated from the legitimate, enrolled device. |

|

|

| I – Information Disclosure (Data Exposure) | Leakage of sensitive data, credentials, or keys through interception, debugging, or insecure storage. | Exposed tokens or keys could enable off-device attacks. |

|

|

| D – Denial of Service (Service Disruption) | Overload attacks, fake signed requests, or signature-verification floods against backend infrastructure. | Backend performance degradation due to signature verification and registry lookups. |

|

|

| E – Elevation of Privilege (Privilege Escalation) | A compromised app or malicious device tries to gain higher access or act as another legitimate device. | Attackers might clone apps, forge device environments, or reuse compromised keys. |

|

|

Architecture: Device-Bound Signing in Practice

Check out the GitHub repo for a reference implementation that puts these concepts into practice.

The sample combines secure device enrollment, device-bound keys, and hybrid signatures using both traditional algorithms (ECDSA P-256) and post-quantum ML-DSA-65 where supported, offering a practical blueprint for implementing device-bound request signing across modern mobile.

Conclusion

Device-Bound Request Signing (DBRS) introduces a fundamental change in how trust is established in mobile ecosystems. By binding requests to the originating device, it moves beyond static credentials to provide verifiable proof of origin. This approach reduces vulnerabilities in token-based models and strengthens defenses against off-device attacks.

Implementing this mechanism requires careful integration, but its benefits extend beyond immediate security gains. It enables a more resilient architecture that aligns with modern zero-trust principles and prepares systems for evolving compliance and threat landscapes. Adopting such device-centric protection is a practical step toward stronger, long-term security.

References

0 comments

Be the first to start the discussion.